The artists associated with the Hudson River School would never have been so successful or, for that matter, earned a living had it not been for the patronage and support of wealthy citizens and public unions to commission these pieces and encourage a wider public audience. The role of the patrons associated with the Hudson River School is markedly different than that of earlier, European patrons. In Europe, traditionally, patrons of landscape pieces were members of the Church and the nobility, who desired depictions that reinforced their power and as such, were usually works that depicted some greater human presence over a tamed nature. In this vain, commissioned art’s purpose was somewhat self-aggrandizing; it was meant to tell a peculiar narrative that was desired by the artist, the patron or the Church. This was not the case for the patrons of the Hudson River School; there was no inherited experience with art for Americans, no formalized associations or expectations and as such, the patrons were psychologically different than their European counterparts. The patrons of this school did not exclusively seek narrative pieces, nor did any painting depict the human as superior to nature, and, interestingly, patrons and supporters of this school were not necessarily rich, at least not by the standards associated by European aristocracy. The American patron was a new type that came from lower or middle class upbringings and became monetarily successful.

One of the most prominent and influential of patrons of the group was Luman Reed. Reed lived the American Dream, in that he grew up poor and eventually became one of the most successful merchants in America in the early 19th century. Reed owns the title as the most powerful patron associated with this school because, not only did he commission masterpieces from Cole and Sidney-Mount, among others, Reed strongly encouraged Durand to abandon his chosen career as an engraver and instead to become a painter and as such, we have Reed to thank for many of Durand’s masterpieces. Beyond commissioning great works from these three artists, not to mention commissioning the Course of Empire (pictured below) series from Cole, Reed created his own NYC gallery to display some of this art, which was turned over to the New York Historical Society in 1858 a few years after Reed’s death. Another patron worth noting in connection to Reed was Jonathan Sturges, a man who shared Reed’s merchant business and his love for this newfound American landscape style.

Thomas Cole, The Savage State – The Course of Empire

There are, in fact, quite a heavy handful of patrons who directly supported these artists. Elizabeth Colt and Daniel Wadsworth are two that deserve recognition due to the contribution to the school that both of these individuals have made. Elizabeth Jarvis, daughter to a middle-class Rhode Island minister, married Samuel Colt, an incredibly wealthy arms manufacturer and inventor of the Colt revolver, in 1856, six years prior to Samuel’s early death at the age of 47. At that time, Elizabeth Colt became one of the richest and most powerful women in America with over $15 million in 1862 US dollars. Unfortunately, two of her sons died and one of her late husband’s main factories burned to the ground in the year following her husbands death. Rather amazingly, instead of hiding behind her wealth with her one remaining son, Elizabeth became one of New England’s leading socialites and benefactors; she sponsored churches, founded community organizations, was named The First Lady of Hartford and more importantly, she collected and commissioned many pieces of art, which were bequeathed to the Wadsworth collection near the end of her life. The Wadsworth collection, or Wadsworth Atheneum, is the oldest public art museum in the entire United States and was primarily founded by Daniel Wadsworth, although contributions from JP Morgan, the aforementioned Mrs. Colt, among others, helped to grow and more or less establish this fine collection of paintings from the Hudson River School. The museum was built and opened in the early 1840s and, at the time, the Wadsworth family was one of the most affluent American families in New England that could trace their roots back to some of the first Puritan settlers. Daniel Wadsworth’s interest in works of the Hudson River School was arguably sparked by his relationship with John Trumbull, famous painter and uncle-in-law to Wadsworth, at the turn of the 19th century. Due to his connection to Connecticut’s high society, the American art world and more specifically, his thoroughly American roots, Daniel was determined to support and develop a truly American artistic style, which is why he commissioned and purchased so many pieces from artists associated with this school. Thomas Cole’s piece below was commissioned by Wadsworth in 1826.

Thomas Cole, Kaaterskill Falls

Elias Magoon, George Featherstonhaugh, Robert Gilmor, Philip Hone, Charles Talbot and Samuel Ward also played their part in supporting the school and the artists associated with it.

A good deal of the responsibility for establishing the encouraging artistic environment that these artists flourished in falls upon The American Arts Union: a subscription based organization that made prints of artists’ work, sent around newsletters to members, and had a gallery, where members could come to the gallery and browse some of the latest works. The above piece, Thomas Cole’s It was founded in 1839 and lasted until 1850 in New York, and was specifically modeled after the Arts Union of London, which was founded just a few years earlier. Although the collective group of members did not sponsor pieces of art directly, they did spread information about and visual depictions of works in this style. The Union connected members to the artists and the art world directly and it widened the audience by making it much easier for citizens to access the art.

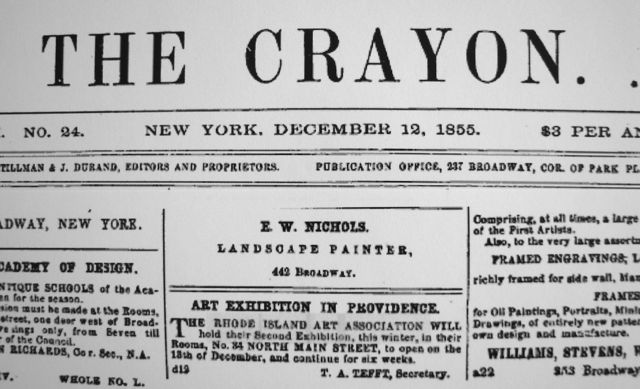

One of the school’s most unique supporters was The Crayon, which, in its own words, was “a journal devoted to the graphic arts and the literature related to them.” The Crayon was co-edited by Asher Durand’s son, John Durand, and in 1855, Asher Durand published nine “Letters on Landscape Painting” in the Crayon. Many other noted artists’ written work from this school, such as Albert Bierstadt detailed writings on his experience out west, were published in this journal. Without all of the aforementioned supporters and patrons, it is without a doubt that some of these masterful works would have never come into fruition.