The Landscape & The Artist’s Environment: When & Where

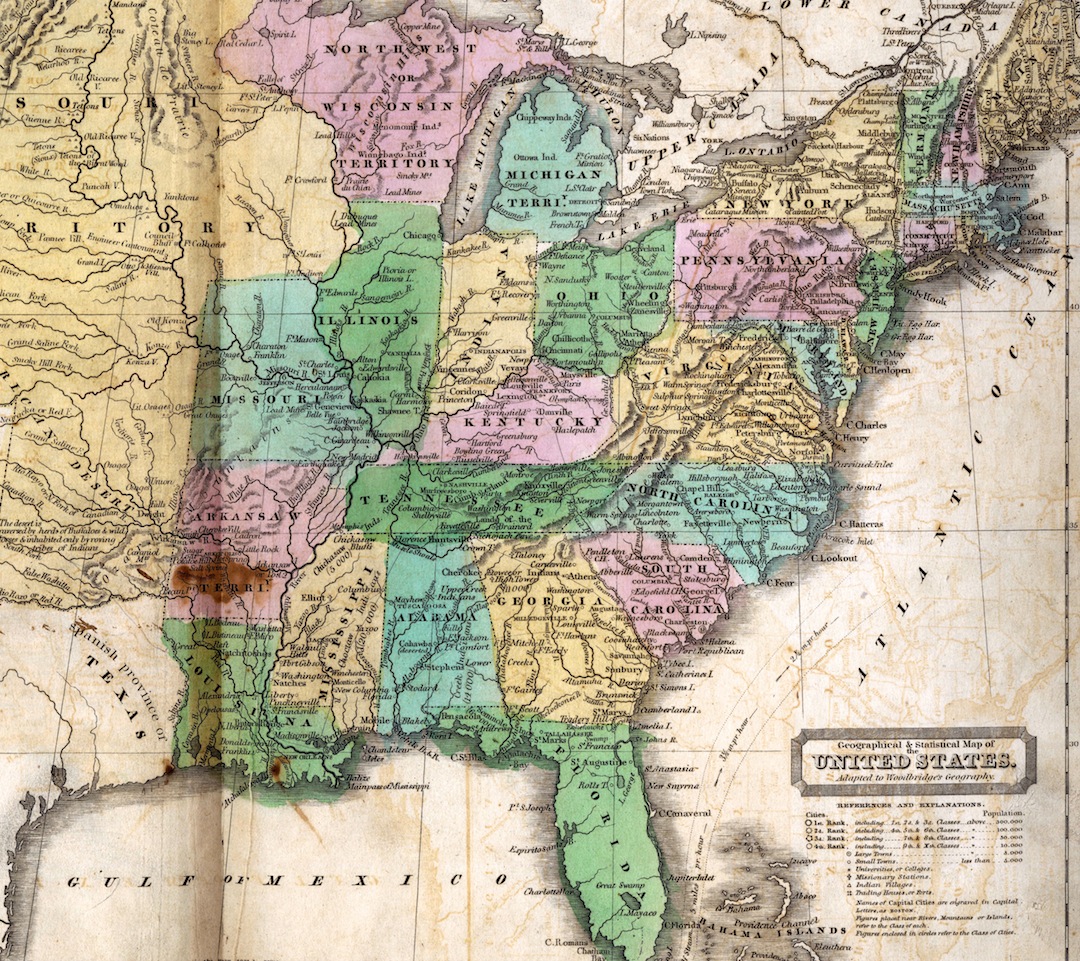

In the beginning of the nineteenth century in America, a sizeable chunk of the American territory was relatively unexplored and undocumented. The same could also be said of the neighboring French, Spanish and English territories, and a good deal of that land was later incorporated into the United States. While the United States government focused on securing more and more territory throughout the 19th century, with the Louisiana Purchase and Missouri Compromise, the invention of the first steam locomotive and the completion of the Erie Canal made it feasible for people and goods to travel to and from the additional land. The vast, unexplored American wilderness was not being particularly hospitable to the expanding population. 1815 was the volcanic winter, one of the harshest winters to date. Six months later, it became the the year without a summer, because a constant dry fog blanketed New England during the summer months. In addition, two major frost events and one snowstorm destroyed the summer’s harvest in May, June and July respectively. Four years later, the world learned of Antarctica and the United States founded Liberia for freed slaves. There were still parts of the world that were uncharted territory, and that idea flirted with every free-thinking individual.

To settlers, immigrants and travelers, the unexplored American landscape offered the physical space necessary for them to expand their philosophical and personal freedoms. For painters, the landscape inspired the development of their skills and style. As wealthy patron, Richard Ray, pointed out in a speech before the American Academy in New York in 1824, “our country affords peculiar advantages. I mean the Landscape-painter…if vastness and grandeur fill his mind – if he can command the rich and golden hues of colouring, let the new Titian touch his pencil on the Catskill mount; or let him, another Claude Lorrain, looking upon its laughing scenes of plenty, shed on them the same delicious repose and serenity, which have been claimed for Italy alone. Or if his half-savage spirit, like Salvator Rosa’s, delights in rocks, and crags, and mountain-fastness, an unattempted creation rises at a distance to invite him. There he may lose himself, till a wild scene of cascades, of deep glens, and darkly shaded caverns, is frowning around him; and though, thanks to our equal laws no bandit is seen issuing from his hiding place, yet there he may plant the brown Indian, with feathered crest and bloody tomahawk, the picturesque and native off-spring of the wilderness.”

The first generation painters of the Hudson River School, the “founding fathers,” predominately painted and sketched in the Hudson Valley, New England and Tri-State regions. In 1840, the American Arts Union was founded, which was a subscription based organization for a fee of $5. The organization provided with subscribers access to their modern art information, access to their gallery and more generally created an atmosphere for the artist, the art-lover and the art-buyer alike. The Union is largely responsible for popularizing this style. In addition, the high society and developing art world in Manhattan gave legitimacy to the school’s rise. The Mexican-American War in 1846 drove thousands of young men out West, expanding the chartered frontier. As the frontier expanded, each new artist who tried to capture the last glimpse of it before the frontier closed at the end of the nineteenth century. As each geologic / natural wonder was explored and translated, whether via oil painted on canvas or topographical lines drawn on a map, and then shared with the public at large, each new and old painter went deeper into the unexplored territory to find new inspiration. Frederic Church, for example, frequently took off for the Caribbean Islands or Latin America.

A map produced near the end of the nineteenth century of the American landscape looks more or less the same as a map drawn today. The Civil War demanded the creation of in volumes of maps and reports on a significant portion of the American territory. The United States acquires Alaska in 1867, finishes the Suez Canal two years later and then creates Yellowstone National Park three years after that. Americans had moved, and were still moving, out into the somewhat decreasing amount of available land. During those years, Native Americans were forcibly removed from their land, and sometimes executed. In 1890, American soldiers murdered somewhere around 200 Native Americans from South Dakota in what is now known as the Wounded Knee Massacre. This horrific event is correlated with the end of the frontier, which is also generally agreed to be in that same year. Furthermore, the art of photography was just coming into fruition and the American public was now familiar with the natural landscape and the associated romanticism. The modern focus of the art world was now turning inward, focusing on human intellectual, individual and industrial accomplishments. Landscape painting ceased to awe and / or interest viewers and more importantly, ceased to inspire the artists. Americans had finished exploring the American West and it was time for different kinds of artwork.

Please Click Here to for the Virtual Tour throughout the Hudson River School!